Politics of Aesthetics revisited in Vaporfornia

Vaporfornia (see addendum) is a surreal dark comedy, fantasy, adventure novel, set in California, which I published about a year ago. The novel revisits themes from my series on Aesthetic Socialism, which is not socialism in an egalitarian sense but rather acknowledges that aesthetics are a form and signifier of wealth, and proposes incentivizing the supply of aesthetic based resources. Since economic materialism is a way to gain access to aesthetics, the hypercompetitive nature of capitalism and problems of elite overproduction, are largely a result of aesthetic inequality. Perhaps a lot of the harshness of capitalism could be eased, if society overall became more aesthetically appealing. Contrasting two different locations, an area where both the built environment and people are more aesthetically pleasing, will just overall feel wealthier, regardless of GDP per capita.

Vaporfornia’s protagonist, Max, has a realization that fictional presidential candidate, Roger Blackstone, has unlocked the key of how to win people over by addressing their untapped desire for positional goods, such as access to people, locations (eg. walkable communities), and things of aesthetic value. Blackstone proposes this utopia where everyone is wealthy, because everyone and everything are aesthetically pleasing. However, this aestheticist ideology gets touchier when applied to people, with eugenic overtones. Access to people, besides places, buildings, and objects, are also a positional good, which includes dating and sexual attractiveness. Obviously physical appearance is a touchy subject and taboo to discuss in polite society. There are plays on incels’ obsession with looks, as Max becomes entrenched in the online incel subculture. However, he is not unattractive, is intelligent and initially very woke, but he is shy, alienated, and mentally unbalanced. The irony is in how incels, who are Darwinian losers, being selected out of the gene pool, are courted to by Blackstone as a constituency, with eugenic policies to beautify the populace, including “open borders for hotties” type immigration policies, transhumanism, and imposing natalism on the rich as positive eugenics, as the wealthier are on average more attractive due to assortive mating. There is this stereotypical image of California’s preppy blonde youth, that is today more confined to a niche elite caste rather than a middle class mass society, as there was in the past, and Blackstone proposes creating more of this demographic.

Another major theme is how subconscious psychological motives and biological imperatives show up in politics and culture. For instance Max’s contemplation that, “Whenever I dream, I can sense what I’m missing out on. Sometimes I see it vividly yet locked out, unable to touch or partake. The energy representing everything I so deeply desire surrounds me, yet I’m still alone in a dark bubble.” Blackstone’s proposals are a sort of alchemy, to tap into people’s hidden desires from their dreams and put together all of the puzzle pieces, as aesthetics, metaphysics, spirituality, social status, sexuality, psychology, and politics are all heavily interlinked. The message from Blackstone is that it is better to more honestly embrace psycho-social motives that come up subconsciously in politics. There is also a satire of the psycho-sexual and aesthetic undertones of rightwing ethnopolitics and their concerns about demographic change. The satire and humor is in how Max approaches these issues from both leftist moralistic sensibilities but also his own psycho-social motives, encapsulated by his “sperg out,” “my own census found a decline by 30% in hot girls over a 4-year period. Maybe this is what Blackstone is talking about when he says that wealth must serve the demographic aesthetic good.” There are also parallels between society ageing and loosing its vitality to the “age pill,” or fear of missing out on youth, and Blackstone’s political promise is to preserve those fleeting dreams of youth, beyond just escapism or the false promise of eternal youth of liberalism, but rather the alternative future that we should have had (eg. Retrofuturism).

There is social commentary on California’s extreme inequality and class stratification. For instance spatial segregation with exclusive resorts, swimming pools, country clubs, private schools, and gated communities, in contrast with homeless encampments. These spaces co-existing, are practically outer-realms, as Max contemplates while sneaking into an exclusive resort, that may or may not be real, “So exclusive that there’s no unaesthetically pleasing gate but you must enter through a secret camouflaged portal that I somehow managed to get through. Might as well be a portal to another dimension.” Max initially approaches these issues of inequality, from an egalitarian standpoint, with his contemplation that “Beauty is unjust because it’s a finite resource. But once I spread it to the world everyone will be equal and free,” and his belief that “aesthetics are a human right.” The question is whether Max’s initial egalitarianism is a façade to mask his own status anxieties about where he stands in the world, status wise, being a neurotic, young, idealistic, liberal, from the downwardly mobile White upper middle class, impacted by elite over production, and being a White male in a hyper woke environment. Max fluctuates back and forth between feelings of guilt for his own “privilege,” and resentment about being excluded by those with status.

The turning point in Max’s thinking, is when he asks himself, “Would Blackstone’s programs spread beauty across all class lines rather than just a luxury reserved for the elites, a kind of aesthetic Marxism?” Though he is unsure as to whether Blackstone’s ideas are compatible with his leftist principles, are they fascist, or perhaps just a capitalist gimmick or scheme to make a fortune, profiting off of every possible market. However, Max starts to embrace Blackstone’s ideas, which could be described as a Third Position or Chad Centrism, and is especially won over by Blackstone’s grand aesthetic visions. The politics of aesthetics could actually benefit the low status, in contrast with economic elites who hoard beauty to themselves. Obviously the poor and low status enjoy the aesthetics associated with wealth and status, even if in a voyeuristic sense, such as the poor visiting wealthy amenities or the incel checking out hot girls. However, Blackstone’s new paradigm stands in contrast with egalitarianism, which tends to bring down aesthetics to the lowest common dominator.

Blackstone articulates his visions through aesthetic imagery to show the kind of society that one would ideally want to live in, with projects ranging from rustic European villages to futuristic skyscrapers, and various retro-futuristic genres. Blackstone also proposes building ethnic enclaves on the theme park model for California, which appeals to Max, both as a liberal who likes diversity, but also the childhood dream of living in Disneyland. Though Max has reservations that this multi-culturalism based upon the theme park model is just regurgitated Jim Crow with a touch of glitz. However, both Blackstone and Max evolve to meet at a position, that is pluralist. The ideal of many people and groups being able to live in utopias that fits their desires, without having to sacrifice, which applies to politics, urbanism, demographics, and aesthetics.

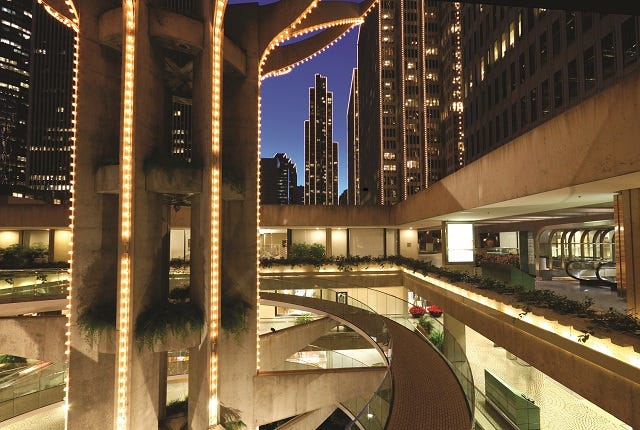

John C. Portman’s Embarcadero Center in San Francisco

Blackstone as a real estate developer, utilizes capitalism to achieve aesthetic visions, that represent a kind of nobles oblige, from past societies. For instance building beautiful monuments and communal public spaces to uplift civilization, that have been lost under liberal capitalism. There is a more promethean quality to aesthetics produced by earlier stages of capitalism, such as Art Deco, Neon signage, and old school Las Vegas, which are in line with what Blackstone seeks to recapture, and the essence of the retrofuturism genre. While capitalism has produced innovation, the problem with capitalism, is in how economic interests commodify all aesthetics for profit. This is relevant to the architect, John C. Portman, whose San Francisco interior urbanism, is also referenced in the novel. Portman was unique in that he was both an architect and developer, thus could implement his own grand aesthetic visions.

There is a lot of political symbolism in architectural aesthetics. For instance a lot of newer minimalistic architecture, such as Silicon Valley tech campuses, sterile hospital-like interiors, and minimalistic mall renovations, as well as the privatization of space, serves to conceal wealth, hierarchies, and power, which is the essence of late stage capitalism. The built environment also impacts the psyche, such as demoralizing, soothing, empowering, or awe inspiring. Some of these minimalist renovations have even been tied explicitly to woke cancel culture. For instance the renovation of LA’s Post-Modernist D.W Griffith inspired Hollywood & Highland Mall, and of the Art Deco Sir Francis Drake Hotel in San Francisco, due to the namesake being a colonizer.

Sir Francis Drake Hotel Neon

There is the tragedy of the starving artist who cannot afford access to beauty, beyond their own work. While Blackstone calls for greater patronage of the arts, unlike the lefty cause of funding the arts as charity, Blackstone is more in line with thinkers like Aleister Crowley, Ezra Pound, Oscar Wilde, and Wyndham Lewis, who believed that artists should be a ruling class or elite caste. Where Blackstone’s philosophy is most at odds with liberalism, is his belief in caste. For instance those who create aesthetics and innovate who must be funded, those who can afford access to aesthetics but don’t create whose economic scope should be limited, the caste of beautiful people who are paid to breed, and then everyone else.

I make the case for aesthetics as a key principle of a radical center, that supersedes capitalism vs. socialism, or the socially liberal vs. conservative spectrum. While the left has traditionally catered more to creative types, much of today’s left views beauty hierarchies as fascist, and Wokeness is overall making everything uglier, functioning as spiritual warfare against beauty. Therefore, there is a case that beauty hierarchies are rightwing, such as traditionalist culture critic, Roger Scruton’s, view of beauty as virtue, or Bronze Age Pervert’s call to restore beauty hierarchies and vitality. While rightwing Trad types are too rigid about aesthetics, it is good to see the right embrace Retrofuturism, much like Blackstone, who is certainly not a reactionary about aesthetics. There are less Trad thinkers, who don’t neatly fit into the left vs. right spectrum, such as dissident feminist, Camille Paglia, who has written about the symbolism of beauty and importance of aesthetics to civilization. Not to mention Oscar Wilde’s philosophy of aestheticism. While I am against beauty relativism, there also has to be room for radical creativity and many niches, a non-egalitarian pluralism.

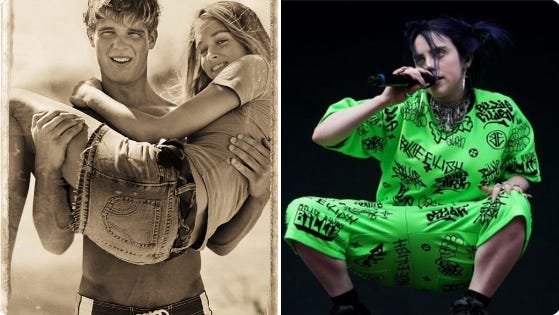

R E T U R N T O T R A D I T I O N (early 00s Hollister Add)

The shift in aesthetic standards is relevant to the body positivity movement, which is a product of liberalism with quasi Christian undertones. For instance beauty is in the eye of the beholder, and never judge a person by how they look. However, the woke war on beauty goes beyond that, to inverted value systems and hierarchies, where ugliness is virtue. While body positivity is primarily about women and does not apply to incels, there are ironic parallels with the incel take on lookism. Another angle is the insane woke hysteria over sexual racism, such as rejecting Eurocentric beauty standards, which is parodied in the book. I remember some celebrity, a while back, getting flack for saying that my heart loves everyone but my penis is racist. Advertisements reflect these cultural shifts, from Abercrombie & Fitch and Hollister, from my adolescence of the early 00s, of blonde preppy youth, then a transition with the Hipster era, American Apparel, which was more diverse yet still emphasized beauty and sensuality, and then woke advertisements of today, which celebrate ugliness. Despite virtue signaling, practically everyone does judge others by how they look. While beauty preferences vary by individuals and ethno-cultural groups, it is clear that evolutionary and hereditarian factors shape these preferences.

Aesthetics can function as a morality that transcends other forms of morality. For instance the debate over nudity should be an aesthetic issue, in contrast with moralization from the Puritanical right and various feminist takes, as well as body positive and liberal hippie cases for nudism. However, one could make an ethical critique of the hypocrisy in how killing a butterfly is considered evil for aesthetic reasons, but people are ok with killing other insects, such as spiders. While people should not base their entire moral/ethnical framework on aesthetics, aesthetics as a value, are far superior to most moral hysterias from both the left and right. The celebration of beauty is more of an aristocratic value, and in Bronze Age Mindset, Bronze Age Pervert makes the case that Ancient Greece, France, Italy to a degree, and Japan, are unique in having a civilizational emphasis on beauty, that modern America certainly does not.

Max is later blackmailed into participating on a show that parodies Blackstone’s aesthetic based politics, with cruel sadistic humiliation rituals. These rituals are for cheap entertainment value, but also perhaps used to discredit Blackstone, and are somehow connected to shadowy elite interests. Max is “set up” to be used in the “seats,” which is something that he initially hears about as an urban legend, where rich snobby cliques exploit and humiliate undesirables. The “seats” are a grotesque allegory on power dialects and social commentary on the extreme disparities in class and status, and the anonymous exploitation and commodification of late stage capitalism. In contrast with hierarchies and ugly realities that are concealed, without being too graphic, one’s place in the hierarchy and power dialects becomes about as blatant as possible, encapsulated by the slogan, “your best is only good enough for my worst.”

The “seats” could also be interpreted as a perverse nobles oblige-based social or political arrangement between those at extreme ends in status, where the low status partake in one of the most subservient and degrading positions imaginable, yet at the same time have access to the intimacy that they have been denied of, and access to those way above their league in status. It is analogous to how house slaves were allowed in mansions, in contrast with today’s atomization, where those at the bottom of society are totally excluded and obsolete, yet granted some illusion of equality. Those exploited in “the seats” take on a eunuch-like role while also having access to the genes that contain the formula for beauty, even if it is via filth, mirroring the eugenic politics and theme of caste.

Beverly Center 1980s

Another metaphorical allegory, is a psychedelic trip-like experience that Max has at the fictional Beverly Experience, based upon the Beverly Center mall near Beverly Hills. While wondering around some dark abandoned corridor, Max stumbles upon a Jenga-like tower made of neon-illuminated cubes of brick glass, that are constantly moving, and changing color. Max notices that each of these glass cubes, contains a particular memory of his, such as lost loves, hopes, and fears, that taunt him about the missed opportunities and dreams, that failed to come into fruition, given a chance to bloom. This was inspired by very hypnogogic memories from early childhood, of the Beverly Center, from the late 1980s, such as of the external glass elevators, with red neon numbers for each level. Being born in 85’, I experienced the 80s in the hypnogogic state of early childhood, which is very different from GenX 80s nostalgia, and explains why the core fanbase of the New Retrowave genre, which reinvented the 80s, were close to my age.

This is relevant to how the Vaporwave genre is not outright nostalgia, but rather saudade, nostalgia for what could have been, in a hypnogogic state. This applies to travel, in how there is this sense of wonder, mystique, and exploration, in childhood, which is latter ruined during adulthood, having Google Maps. Even if the place does not change, it is our sense of perception that shapes our reality. This explains how online political discourse is very much about distorting or creating alternative realities, which can be a cope, but is also a product of postmodernism. It is also relevant to the New Age concept that any reality is possible, via creative thinking, affirmation, and manifestation. Vaporfornia deals with these themes in regards to Max’s life trajectory, as well as the theme of California’s and American society’s decay. For instance, alternative trajectories, or alternative timelines, exist as metaphysical realms. Certainly, it is not ironic that California has long set the masses’ perception of reality via Hollywood.

Mount Diablo

Vaporfornia also serves as a travelogue for California, with graphic architectural depictions throughout the book, including San Francisco, Max’s home in the East Bay suburbs, Mount Diablo, Santa Cruz, Modesto, the Sierra Nevada Mountains near Yosemite, Reno Nevada, and the LA area, including Beverly Hills. While the depictions of the Bay Area are more realistic, the LA segment is more of a surreal, or even Lynchian, fantasy realm, where Max is taken to partake in the depraved show. I would recommend Vaporfornia for those who enjoy travelogues, fantasy adventure, dark comedy, social and political satire, and dramatic irony, but it is not for those who are easily offended.

Vaporfornia is available in paperback on Lulu.